DATE

12/8/25

TIME

9:35 PM

LOCATION

Oakland, CA

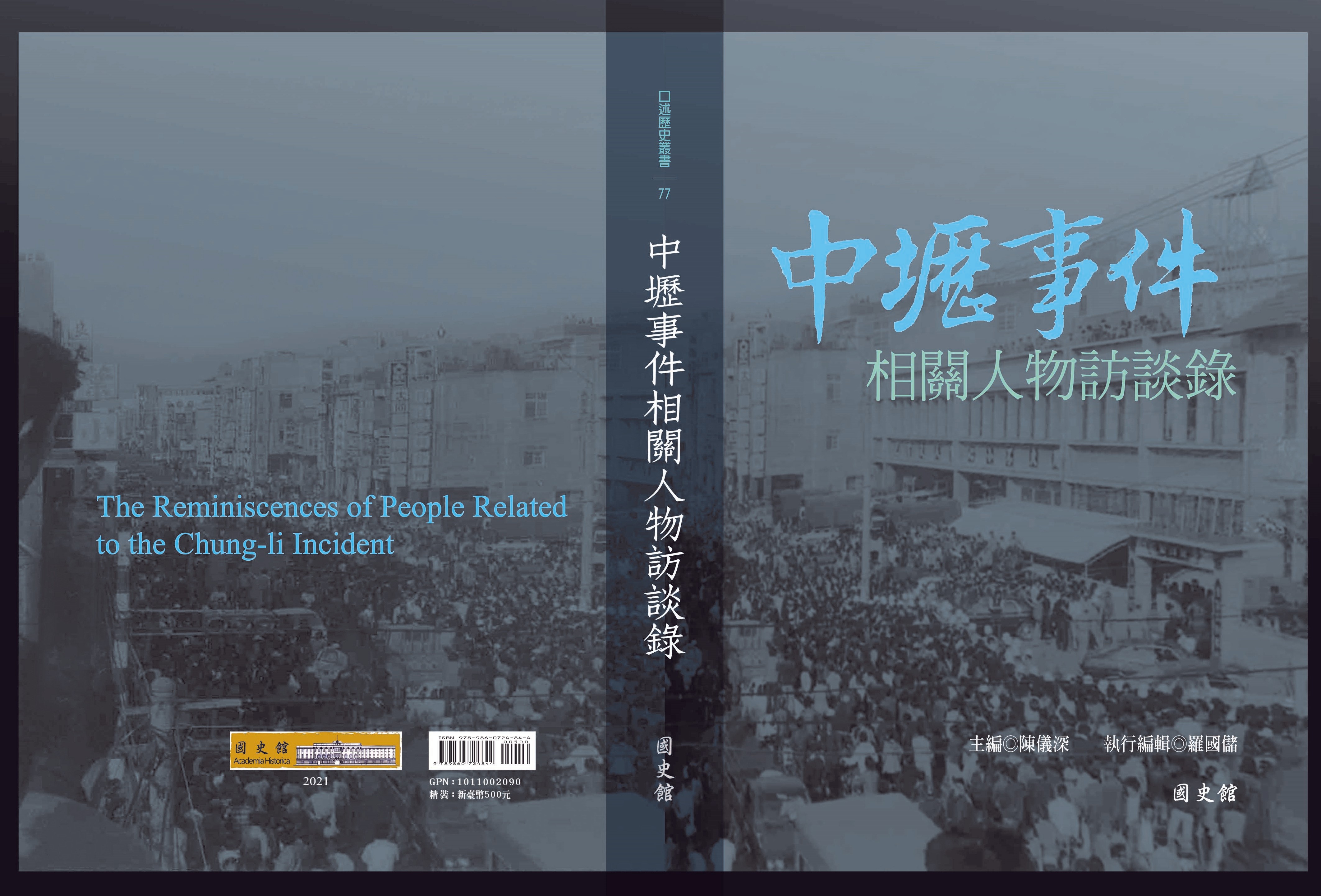

Taiwan’s Path to Democracy(iii): Zhongli County Election Incident

台湾民主历程(iii):中坜事件

Preface:和ChatGPT合作完成。

1977 年 11 月 19 日,桃园县在戒严体制下举行县长选举。那一年,脱党参选的许信良在地方上声势很高,让桃园成为全国焦点。但在投票当天下午,中坜国小的投开票所爆出疑似作票,也成了整个事件的导火线。根据当时的报道与后来各种调查,投票所负责监督的校长,被民众当场指控妨碍投票流程,甚至塞票。更让人不满的是,检察官到场后,把检举舞弊的民众带走调查,却没有把被指控舞弊的校长撤职处理。这在现场群众看来,就是司法和行政单位在袒护权力方,完全没有公正性。这样的处理方式立刻激起更强烈的不满,事件也因此一步步升级。

消息在中坜迅速扩散,越来越多的居民赶到投开票所要求查明舞弊。警方和群众发生推挤与冲突,秩序开始失控。下午后段时间,有民众开始对投开票所丢掷石块,第一次出现实质暴力行为。随着冲突扩大,抗议行动一路延烧到中坜警察分局。傍晚时,数千名民众已经把分局围得水泄不通。对于戒严时期的台湾来说,这种规模的选举抗争非常罕见。群众要求警方解释选举争议、调查相关官员的行为;部分人向分局投石、破坏现场的警车,使整体气氛更加紧绷。警方先后发射催泪瓦斯,试图驱散人群,但完全没有办法恢复秩序。晚上七点多,现场传出枪声。根据后来调查,至少三名民众被击中,其中两人死亡:中央大学学生江文国、十九岁的中坜青年张治平;另一名少年重伤。枪击事件使情势彻底失控,也成为这场抗争发展的关键转折点。多年后的资料显示,谁下达开枪指令、是谁扣的板机、责任归属如何,始终存在争议,也被纳入转型正义的调查重点。

枪击后,群众情绪急遽恶化。许多史料显示,中坜分局的警力在晚上某个时间点大规模撤离。之后,分局建筑遭到破坏并被纵火。大火持续两个多小时,烧毁了分局主楼、警察宿舍和附近设施。在戒严管制下,当时的官方报道大多把事件定调为“暴民滋事”。但学界后来的研究普遍认为,这不是单纯的破坏行为,而是长期累积的结构性问题爆发:选举不公、法程序失灵、官民之间的信任崩坏,以及威权统治下压抑已久的反弹。事件平息后,为了缓解民怨,政府决定重新统计桃园县票数。许信良最终胜选。这被许多研究视为国家机器在压力下的一次被迫让步。中坜事件也因此常被视为台湾民主化的重要前奏:这是战后第一次因选举舞弊而爆发的大规模群众抗争,也让社会看见所谓“有限选举”所面对的合法性危机。

事后,学者普遍把中坜事件视为后来美丽岛事件以及 1980 年代街头运动的前导。它显示:台湾社会已经不再被动接受单向度的威权秩序,而是开始质疑、挑战国家权力的滥用。1980 年春天,《美丽岛》的八位主要党外领袖在军事法庭受审。这是国际高度注目的政治审判,美国媒体、国会、人权组织全都介入。虽然最终判刑,但反效果非常明显:党外力量被“合法性化”,民众第一次明确看到民主运动的核心人物,台湾社会将这些人视为“民主象征”,威权镇压反而培养了下一代民主领袖。

美丽岛大审期间,林义雄家在白天遭遇灭门血案,母亲与双胞胎女儿遭刺杀。当时林宅正被警备总部“监控”,却完全未阻止凶案。案子至今未破,社会普遍认为是情治系统的政治恐吓。这次事件的影响巨大,台湾社会对威权的恐惧达到顶点,对党外群体来说,政治改革必须成功,否则永远会有人受害。此后的1981至1982年间,陈文成命案等政治事件持续累积。其中,陈文成是美国留学生,上文提到过,他当时从美国返台,被警总约谈,隔天死于台大校园。官方宣称自杀,但漏洞百出。同一时期,还有作家或异议人士失踪、死亡的事件,使社会进一步失去对情治系统的信任。威权政府的正当性从此开始连续下降。

党外人士开始建立长期记者会、律师团、杂志群与竞选团队。《美丽岛》杂志虽然被查禁,但留下巨大思想影响力。新的杂志开始出现,如《深耕》《蓬莱岛》《八十年代》《现代妇女》,他们成为反对思想的基地。1984年,美籍华裔作家江南因批判蒋经国政权,被台湾军情局指挥黑帮在美国暗杀。这是威权体制最严重的国际丑闻之一。美国 FBI 破案后,白宫震怒,派人到台湾施压,蒋经国不得不处理情治系统。这次之后,台湾情治系统遭到整顿,蒋经国意识到威权不再稳固,改革派在党内强化自身声音,国际社会明白台湾威权已走到尽头。

On November 19, 1977, Taoyuan County held its magistrate election under martial law. That year, independent candidate Hsu Hsin-liang had gained strong grassroots support, turning Taoyuan into a national focal point. But on the afternoon of election day, allegations of ballot tampering at the Zhongli Elementary School polling station triggered what would become the Zhongli Incident. According to contemporary reports and later investigations, the school principal—serving as the polling supervisor—was accused on the spot by voters of interfering with voting procedures and even stuffing ballots. What angered the public further was that when prosecutors arrived, they removed the citizens who reported the fraud but allowed the accused principal to remain in his post. To the crowd, this signaled that judicial and administrative authorities were protecting those in power rather than acting impartially. This perception immediately intensified public resentment and pushed the situation toward escalation.

As news spread rapidly through Zhongli, more and more residents converged on the polling station demanding an investigation. Confrontations between police and citizens quickly broke out, and order began to collapse. Later in the afternoon, some people started throwing stones at the polling station—marking the first instance of physical violence. As tensions continued to rise, the protest spilled over to the Zhongli Police Precinct. By dusk, several thousand people had surrounded the precinct. For Taiwan under martial law, protests of this scale over an election were extremely rare. The crowd demanded that police clarify the election irregularities and investigate the officials involved. Some people threw rocks at the precinct and damaged police vehicles, further straining the atmosphere. Police fired rounds of tear gas to disperse the crowd, but failed to bring the situation under control.

Shortly after 7 p.m., gunshots were heard. Later investigations confirmed that at least three civilians were shot, two of whom died: Chiang Wen-kuo, a student at National Central University, and nineteen-year-old Chang Chih-ping of Zhongli; another youth was seriously injured. The shootings caused the protest to spiral completely out of control and became the critical turning point of the confrontation. Decades later, questions about who gave the order to fire, who pulled the trigger, and how responsibility should be assigned remain unresolved and are central to transitional justice inquiries.

Following the gunfire, public anger surged dramatically. Many sources indicate that police withdrew en masse from the precinct at some point during the night. The building was subsequently damaged and set on fire. The blaze lasted more than two hours, destroying the main precinct building, police dormitories, and nearby structures. Under the restrictions of martial-law-era information control, the authorities framed the event as a “riot by violent mobs.” However, later academic studies broadly agree that the incident cannot be reduced to simple destruction of property; rather, it reflected the eruption of long-accumulated structural tensions—electoral injustice, procedural failure, the collapse of trust between officials and citizens, and the backlash against prolonged authoritarian rule.

After the unrest subsided, the government ordered a recount of ballots in an effort to appease public anger. Hsu Hsin-liang ultimately won the election. Many scholars view this as a rare moment in which the state, under immense social pressure, was forced into concession. The Zhongli Incident has since been widely regarded as a prelude to Taiwan’s democratization: it was the first large-scale popular uprising triggered by election fraud in the postwar era and revealed the legitimacy crisis facing Taiwan’s system of “limited elections.”

Subsequent research commonly interprets the Zhongli Incident as a precursor to the Kaohsiung (Formosa) Incident of 1979 and the street protests of the 1980s. It demonstrated that Taiwanese society was no longer willing to passively accept a one-way authoritarian political order and had begun questioning and challenging abuses of state power.

In the spring of 1980, eight leading figures of the Formosa Magazine movement stood trial before a military court. This became one of Taiwan’s most internationally visible political trials, drawing close attention from U.S. media, Congress, and human rights organizations. Although the defendants were ultimately sentenced, the trial had the opposite effect of what the state intended: opposition leaders gained public legitimacy, and for the first time, citizens clearly recognized the key figures of the democracy movement. These individuals became symbols of democratic resistance, and authoritarian repression inadvertently helped cultivate the next generation of democratic leaders.

During the Formosa trial, a major political shock occurred: the Lin family massacre. Lin Yi-hsiung’s mother and twin daughters were brutally murdered in broad daylight. At the time, Lin’s house was under surveillance by the Taiwan Garrison Command, yet nothing was done to prevent the attack. The case remains unsolved, and the public widely believes it was an act of political intimidation by the security apparatus. The incident had enormous psychological impact—public fear of the authoritarian state reached its peak, and for the opposition, democratic reform became a matter of survival rather than ideology.

In the following years, political incidents continued to accumulate. The 1981 death of Chen Wen-chen, a U.S.-based Taiwanese scholar, became another watershed moment. As mentioned earlier, Chen was interrogated by the Taiwan Garrison Command after returning to Taiwan, and the next day was found dead on the National Taiwan University campus. The government declared it a suicide, but glaring inconsistencies immediately undermined credibility. Around the same period, several writers and dissidents disappeared or died under suspicious circumstances, further eroding public trust in the security apparatus. The authoritarian regime’s legitimacy began a steady decline from this point onward.

In response, opposition activists built more durable organizational structures—press conferences, legal defense networks, magazine groups, and campaign teams. Although Formosa Magazine was banned, it left enormous intellectual influence. New magazines such as Deep Plowing, Penglai Island, The Eighties, and Modern Women became important forums for dissenting ideas. In 1984, Taiwanese-American writer Henry Liu (Chiang Nan) was assassinated in the United States by gangsters acting under orders from Taiwan’s Military Intelligence Bureau, after publishing works critical of the Chiang Ching-kuo regime. This was one of the most severe international scandals of Taiwan’s authoritarian era. After the FBI solved the case, the White House expressed outrage and exerted direct pressure on Taipei. Chiang Ching-kuo was forced to discipline the intelligence agency, and the internal contradictions of authoritarian rule became impossible to ignore. Reformists within the ruling party gained strength, and the international community recognized that Taiwan’s authoritarian system had reached its limits.